|

||||

|

|

Imagine rural Switzerland of the last centuries. Hills and meadows, separated by rather small forests - but quite densly populated, farms and ranches everywhere. It's the environment we read about in Jeremias Gotthelf's novels and stories and which brought out breeds of sturdy and handsome dogs. Used to drive cattle, to draw carts and to protect farms and properties in rural Switzerland! One of them is the "Grosser Schweizer Sennehund" (GSSH), - or Greater Swiss Mountain Dog (GSMD)

Our family on a walk in upper Aargau In contrast to many other mollossoid breeds, these dogs are free of any structural exaggerations and represent the old type of the farmers and butchers dog of previous times. They are famous for their outstanding character: Calm, self confident, friendly and docile but devoted and fearless if needed.

If the reader is interested in Swiss rural culture of the past, I heavily recommend the open air museum "Ballenberg" in Brienzwiler not far from Interlaken. On a vast territory old Swiss farmhouses are reconstructed and fully accessible. Pluto in front of a beautiful Bernese "Bauernhaus"

|

|||

|

Introduction The early days: cattle or cowherd dogs (Küherhunde) There is evidence from early paintings and

written testimonies that large strong dogs were kept all over Europe but mainly in formerly celtic territory

to protect property, drive cattle, pull carts and could be used

to hunt wild boars, bulls and bears. These dogs were known as Matins

in France and Belgium, as Metzgerhunde or Hofhunde in the German

spoken countries and as Küherhunde (cowherd dogs) in rural Switzerland. A comparison of the typical larger type cowherd dog skulls with specimens from dogs from the St. Bernard Hospice show little morphological difference, confirming the view that a relatively uniform population of “farmdogs” was spread over the main Alpine area.

Typical farm dogs used for drawing a milk kart (Source: old postcard) The dogs of the "Hospiz" at St. Bernhard In 1851 a certain Mr. Richardson wrote that the Monastery in St. Bernard had imported British Mastiffs in 1660 and kept them as watchdogs. This would explain to some extent the scattered occurrence of a more mollosoid skull type seen in the Albert Heim collection, but it is very doubtful where this information came from. There is no such evidence in the records from the Hospice. It is, however, believed that the first dogs were kept at the Hospice between 1660 and 1670 and these first Hospice-dogs were used as watchdogs. A painting from approximately 1690 shows two dogs,

red and white spotted, from the Hospice which are described as "Küherhunde"

! (cowherd's dogs) with slightly heavier heads. The first written

reference to dogs at the Hospice comes a few years later in 1703

describing using a dog to turn a meat skew in the Hospice kitchen. Around 1850 the public interest in St. Bernard dogs suddenly increased. It was a master butcher close to Berne who started to breed with the dogs from the hospice. He was targeting for a type of dog close to the famous dog 'Barry' who saved many lives during his years of duty at the hospice. Many photos show that he was quite successful in his approach. But soon the public interest showed more inclination towards the heavy-headed Mastiff-like dogs as bred by others and strongly favoured by British fanciers. Incredible prices were paid for good dogs. It is no wonder that many red and white larger cowherd dogs have been sold as true St. Bernards by their owners

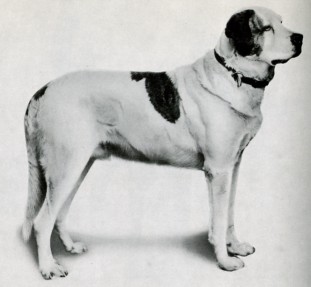

A beautiful Schumacher dog, Barry-type, around 1890 (Source: Räber: Schweizer Hunderassen, Albert Müller Verlag) .It was still not possible at that time to

distinguish between the St. Bernard dog and the large “Sennenhunde”

except for artificial definitions of colour of provenience.

f

Dogs from the Schumacher kennel. Note the black and white "St. Bernhard" The foundation of the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog breed Around 1910 many red and white farm dogs were

probably absorbed into the St. Bernard breed and among the remaining

farm and butchers dog population the tricolour colouring was without

doubt the most beautiful combination and fitted into the newly created

family of Swiss mountain dogs. .

The picture shows a collage of paintings collected from members of The gsshwwdb forum (see link at the bottom) which are dated between 1620 and the 19th century. Most of them are of Flemish and French origin It was a somewhat 'by chance' decision to select

animals with the probably nicest colour combination and breed them

towards a unified appearance. Any other occurring colour could also

have been chosen but this was not the case. A different view is given in the dissertation of Margrit Scheitlin. She follows the lines of early authors (Loens (?), Goetz 1834) who express the the butcherdogs of northern and mid-Germany were mostly black and tan with additional white markings. The occurrence of multi-coloured dogs with an otherwise typical GSMD appearance around 1900 as described by Heim and others is explained with the hybridising with other, imported breeds being en vogue during that time. I do not favour this explanation. St. Bernard dogs derive from the Swiss cowherd dogs. The earliest painting in the hospice is showing as early as 1690 rend and white spotted dogs, long before dog breeding was fashion. The Development of the Breed World War II saw a boom in the breeding of GSMD'ss as they were used as draft dogs in the military service. In the fifties obviously many dogs had insufficient colour. The black was not pure and the brown markings were often yellow. To improve their colouring crossbreeding with a Bernese Mountain Dog (BMD) was performed. Räber states that the offspring, although beautifully coloured with short hair, lacked gait, bite and character. It was for this reason that these dogs were avoided in the use of breeding and so their genetic influence disappeared and the whole action was considered a failure.This seems to be wrong, although it is consistently repeated in many later books. The mating of the BMD Dursli von der Holzmühle with the GSSM bitch Berna von Birchacker resulted in the male Durs von Birchacker. After 4 generations this hybrid already has more than 60 descendants among them, for example, Zarass von Fryberg. Zarass alone has, again 4 generations later, hundreds of dogs in his posterity, among them some champions. So it would be hard to find one dog today, that does not have the blood of this crossbreeding in it's lineage ! Therefore, it seems the arguments against crossbreeding can hardly be maintained based on these facts. A problem that was later faced was the lack of size. In the seventies many dogs were at the lower limit of the standard. Räber proposes a cross breeding with symmetrically marked St. Bernards - I don’t know if this was ever tried. Räber states that from the first 21 dogs in the

Swiss stud book only 7 have given their genes to the present GSMDs.

By browsing the Grosse Schweizer Sennenhunde - Greater Swiss Mountain

Dog World Wide Database (https://www.gsshwwdb.org/index2.html) I

found 8 unique dogs of unknown origin as founders of the breed being

traceable back from today’s dogs. But this gives us a wrong impression.

There are many more founders of the breed as can be seen in the

pedigree of Alex von Fryberg as given in the doctoral thesis of

Scheitlin. There I counted 19 dogs, many of them not registered

(probably not tricolour). Alex's line can be followed through, e.g.

over Oskar von Schwärtzenberg till the present populations.

What can also be seen is that there were many more dogs in the beginning,

some of them never bred, and others going into dead-end lines which

faded away after a few generations, probably due to colour or structure

oddities. A probably more severe habit is the custom to use only champions as stud dogs. Thus very few male dogs are ancestors to a multitude of pubs. Genetic diversity is in this case mostly transmitted by the "mothers". But thid was not enough ! Today we are striving to use as many studs as possible and every owner of a GSMD is encouraged to go through the "Ankörung", the health and character test of the club. The strict limitation of coat colour in itself is no problem but it limited the number of usable dogs to found the breed bringing us to the main problem for the future which is the reduced gene pool, or better, gene puddle. It is well known that inbred populations exhibit

certain traits that are not found in normal out bred populations.

This is because breeding among closely related individuals increases

the probability of matching up recessive alleles. (An allele is

any one of a number of alternative forms of the same gene occupying

a given locus (position) on a chromosome, from Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia). In normal out breeding populations, these recessive

alleles, often deleterious, are masked by normal dominant alleles.

Inbreeding in laboratory populations is consistently used to uncover

unusual recessive traits that a population carries in its gene pool

but rarely expresses..." (Lester & Bohlin, 1989). This can mean that more negative dispositions

will be uncovered in the form of unwanted traits, organical misfunctions

and loss off overall vitality. For those genes that establish breed identity, there will be markedly less variability within a breed than within Canis familiaris as a whole. The tricky part is restricting variability for those genes that make a breed distinctive without sacrificing the variability/diversity that is necessary for good health and long-term survival of the breed. In many cases, this has not been achieved, and we are now paying the price in terms of high incidence of specific genetic diseases and increased susceptibility to other diseases, reduced litter sizes, reduced lifespan, inability to conceive naturally, etc. (Prof. John Armstrong). We should prepare now for the future.

The following suggestion should by no means be regarded as a substitute for our beloved breed. It should be regarded as a pool from where, in future, tricolour dogs may be chosen with a largely expanded gene-pool, if needed, and used to freshen up the home-breed. My proposal is to re-establish the original variety

of Alpine farmdogs or cowherd dogs. This could be achieved by crossbreeding

GSMD’s with the breeds available today which are closest to the

present Swissies. Candidates are proposed in order of preference: The target would be a dog with the approximate physical features of a GSMD, all colours allowed except albinism. Of first importance is a good character ! Even the healthiest dog cannot exist in today’s society if it is considered a threat ! The next and also very important goal is health, followed by functionality and then beauty. The main breeding stock should come out of GSMD’s. Crossing with the other defined breeds should always be allowed with all dogs being tested for character and health issues. In the following section we will discuss some coat colour genetics. It can be stated that even after the mentioned cross-breeding, many offspring dogs will be still tricolour (homozygous!) and could be used, if wished, to breed back into the GSMD breed. There is no danger of loosing the white markings.

The closest relatives of the GSMD showing the colours of the old "Küherhund": Top left a Berger des Alpes, smaller, colours black and tan (like the Rottweiler) and tigers, top middle, a Mastin espagnol, a bit heavier, top right: extremely close to a red-white GSMD but a bit larger, a Broholmer, bottom left a Tosa Inu, not very consistent as a breed, this one is a bit lighter than a GSMD and another, grey M. Espagnol

Räber dedicated one chapter to the coat colours

of all Swiss dog breeds discussing the different factors playing

a major role…… Generally colour in the skin and hair of any being

is determined by pigments, small particles which absorb, transmit

or reflect light depending on their size, shape and material. The

pigment is called melanin and exists in two different types, namely

the black eumelanin and the reddish phaeomelanin. The shape and

distribution of the pigment particles within a hair determines any

colours we know from solid black over all shades of brown, blue

and red to cream and white. These factors are determined by a genetic

code in a chromosome. Very briefly: Imagine a chromosome like a string of pearls of different materials. A pearl of one given material stands for a gene. Modifications of pearls of the same material, say differing size, are called alleles. A locus is a defined and fixed place on this string for one pearl, labelled with letters, on which you can have different sizes of a pearl (gene and allele), of one given material, defining one characteristic of the dog. Say at one locus you may choose between 3 different pearls made of wood, at the next locus you may choose between 5 different pearls of coloured glass, etc. The pearls (alleles) at one locus may therefore have different sizes which manifest a ranking. Say, the biggest one is the most dominant one, the smallest the most recessive one. The alleles are labelled with the locus letter, mind the case and possibly a superscript, e.g. ay. In a mating the sires contribute each one string now, which is an arbitrary mix of their own two strings. So one string from the father and one from the mother form the code for the new pup, and, lets say, the two strings lie next to each other. From each string (chromosome) now the bigger (dominant) pearl (allele) at one locus dictates the characteristic which will show up in the pup. The situation is complicated by the fact that some pearls at one locus dominate even pearls at an other locus, such a gene is called epistatic. This means now that if an allele is the most recessive on a locus, say the black and tan allele in the A locus, then we know that in both chromosomes (strings) there must be the black and tan allele (if it was only present in one, it would be dominated by the other). This is called homozygous inheritance and all future generation dogs will consistently show this characteristic. On the other hand if say a dog carries the at allele but also the more dominant ay allele, the dog will show the ay colour but will inherit this colour heterozygous. This means if this dog one day mates with another dog with the same recessive at allele, in some pups two at alleles will end up in his pair of chromosomes and the dog will exhibit the black and tan colour. Recessive genes can be hidden for generations, however, when they do show up, they inherit homozygous, which means: pure. Genotypes and phenotypes The proposed string of alleles = the ideal genotype

for all Swiss Mountain dogs having the correct colours = the phenotype,

is shown in the middle of the graph. The font colour green makes

alleles in their most recessive form, orange indicates an intermediate

form, black the top dominant type. The other most typical gene is in the S locus and is called Si (Irish spotting) defining the white marks. This gene is present in all mountain dogs and many others including the Broholmer. As it is recessive to the solid colour allele S it will also consistently show in all future generations. Therefore the two most important coat colour characteristics will be easily selectable and be bred in homozygous, that is pure stage. At the S locus there are more recessive genes postulated, e.g. the Sp allele which would cause the white markings to expand to 50% coat area or even the Se allele resulting in white dogs with coloured spots around the ears and the tail. I suggest the action of another, yet not understood gene that steers the expansion of white when Si is present. Räber describes a continuous coat colour dissolution in early St. Bernards breeding, which suggests a gradual transition from Si to Sp to Se hence giving rise to my proposal. The alleles at loci B, C and D cause in their recessive forms some alteration to the melanin pigments resulting in colour changes towards lighter intensities. There is evidence that they are present in the breed. From time to time blue Swissies are born having a dd allele pair. Räber reports about a beautiful havanna (brown) GSMD Fabian von Kleinroth. The havanna colour is accepted for the Appenzell Mountain dog. At the E locus, the most recessive allele would be e, but ee is epistatic to K and A. (The existence of the K locus is not unquestioned, dominant black K was earlier proposed to be on top of the A Locus as As) This means that a dog having ee will not produce any eumelanin pigment therefore no shades of black, havanna and blue in this hair but only red and yellow phaeomelanin resulting in a red and white Swissy.

Two beautiful red Greater Swiss Moauntain Dogs Type "ee" seen at the National "Ausflug" 2005 Hidden K and M alleles cannot be present except when a mutation occurs or they are crossbred into the breed. K would cause all black dogs, M the spotted merle coloured individuals. Finally T would give rise to ticking within the white areas, a feature we know from Swiss Hounds Open questions in colour genetics The allele Em dictates a fawn coat and a black mask. (Although the placement of this allele is not undisputed; some authors place it in an own super-extension locus). Obviously the spotting gene Si is stronger when we see in St Bernards where the muzzle remains white and the black mask shows up only in the eye region. Räber mentions that the black dots, often found in the white around the muzzle are the remainders of a black mask. The E locus is said to be epistatic to the A locus therefore a combination of Em with at will result in a fawn coat with the black mask. Therefore I suggest that the black skin spots in the white area have a different origin. An early GSMD (tricolour) is reported to have offspring with yellow coats and black masks. This seems impossible to me if the bitch was also tricolour. The coat colour of the bitch is not described therefore it must have been a dog carrying the Em allele. A further point is the sometimes occurring blue eyes with otherwise normal coloured tricolour dogs (no merle, no dilution etc), I guess this comes from a different specific eye colour gene. In the future, molecular genetics will shed light on the questions which have not been solved by classical genetics. I guess we will end up with many more loci, genes and alleles and many more chapters about inheritance to be rewritten.

http://www.bastian-net.com/mtdog.htm one of the best links from the US woodcarver

and GSSH fancier Jonathan Bastian The pictures on this page are either self made or from my collection. I tried to find the owners to ask for permission. Thanks to Doris Meier, Mike Rossi and others I will soon quote here.If you see any picture one this page you have the copyright for please contact me.Unfortunately the publisher of Raeber's book does not exist anymore and I did not find any declaration of who got the rights now. The copyright of any content of this page is with the author Dr. Joachim Schoelkopf. For emailing me please go to www.pipidae.de there you will find links to email me directly. |

||||

Copyright (c) Interfaze.ch. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs

Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs